William Anthony (1934-2022)

William Anthony

Photo: David Plakke

Many years ago, so I remember as if it were yesterday, I went to one of those small Chelsea galleries on an upper floor off of tenth avenue, looked at an image parodying Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box and laughed aloud. And was jokingly rebuked: ’Don’t you know that this is an art gallery?’, the person at the desk asked me. That’s how I came to meet Bill Anthony, who became a friend. And that’s why, to the right above the computer on which I am writing, I have his drawing after Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Gianciotto Discovers Paolo and Francesca, (1819). But where Ingres’ two doomed Italian lovers are impossibly elegant, Anthony shows the most awkward two people imaginable making out. For reasons that I don’t claim to fully understand, humor in visual art is a surprisingly neglected topic.

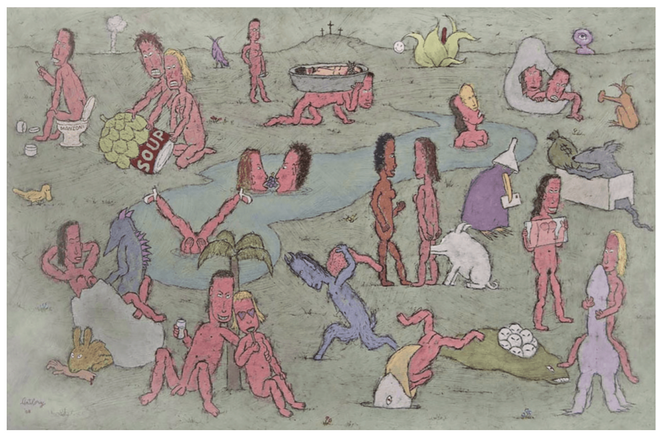

Always mischievous, but never malicious, Anthony got the ideas for his art from teaching beginning drawing students. They drew heads too large, arms and legs too small, and so he appropriated their style for his parodies of old master, modernist and contemporary art. Thus in his Men of Avignon (1997) Picasso’s women are replaced by five skinny naked man. In his Just What is it? (2021), Richard Hamilton’s famous pop image Just What is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, so Appealing? (1956) is redone with a female body builder replacing Hamilton’s male weight lifter, and Anthony’s own art on the walls replacing Hamilton’s examples. The Red Studio (1994) redoes Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911), with the pictures within the picture done, naturally!, in Anthony’s inimitable style. And in Dance (2016), six happily moronic looking pink dancers take the pose of Matisse graceful figures in Dance (1909-1910). The ungainly Giorgione Girl (2008) satirizes Giorgione’s great The Sleeping Venus (1510); Balthus Baby (2000) turns that painter’s pubescent femme fatale into a simpleton; and Laocoon (2011) redoes the very famous ancient Greek sculpture, Laocoön, with the three emaciated men struggling with a skinny blue snake. These examples all come from a recent book, Deviant Draftsmanship. And Anthony also did political history, in his earlier books War is Swell: A kids Idiotic Vision of WWII (2000) and Biblical Stories (1978), a book that impressed Warhol. And he presented politics, as in his politically incorrect Requiem for a Retard (2019), in which a man about to be electrocuted who is eating his last meal asks, ‘What’s for dessert?’ And I love his three drawings (1996), The Effects of Masturbation on Boys (blindness, hairy palms, insanity). Anthony also did caricatures of well known images by Caravaggio, Giorgio de Chirico, Degas, Ensor, Eric Fischl, Gainsborough, David Hockney, Magritte, Sigmar Polke and Tom of Finland. No artist, however famous or dignified, was beyond his reach. Like one of the great old masters, he thus created in his art a whole parallel universe, with everyone ungainly. All of his figures, male or female, look silly; every one of them appears to be a complete idiot.

We are accustomed to paintings with esoteric symbolism or recherché subjects that are not easy to explain. But why are these simple-looking drawings funny? If you don’t know the artworks of Balthus, Richard Hamilton or Giorgione, then it would be impossible to find these images funny. Just as blasphemous jokes only are amusing to people within a religious tradition, so Anthony’s caricatures mostly only make sense to people within the art world. Imagine that some impecunious curator who cannot afford to exhibit original paintings, substitutes instead images by failed art school graduates, thinking that they are as good (I.e. as bad!) as Anthony’s works. This exhibition would a failure, for no one wants to see work by mediocre artists. If a man stumbles in the street, we rush to help him up. But when a great clown does a pratfall (I think, for example, of the great clowning of Peter Sellers in The Pink Panther (1964)), then we applaud his excellent performance. Analogously, although Anthony’s works may be visually indistinguishable from mediocre student works, they, in fact, deserve praise, for they are serious artworks, the product of a gifted draftsman. It takes a great deal of skill for an expert draftsman to make inept drawings. Comedy involves a complex attitude towards what we experience.

What is at stake, I wonder, in Anthony’s making fun of art? Some plausible theories of humor focus on aggression. Was Custer’s last stand funny? Obviously not, but Anthony’s Custer’s Last Stand (1984), with the troops and native Americans alike depicted in his usual fashion, is hilarious. His image turns this tragic disaster into a comedy, perhaps because confronting the whole story of American imperialism now makes us uneasy. Capitol punishment is reprehensible, and so Requiem for a Retard is funny because it relieves us momentarily from acknowledging that fact. It’s hard to imagine a more serious myth than the Biblical story of Samson and Delilah, but his Samson and Delilah (2011), which has an idiotic-looking Samson checking his haircut in a mirror, while Delilah holds the scissors, is a hoot. Here, maybe the problem is that the idea that getting a haircut could cause you to lose your strength is preposterous. But I can’t explain why Anthony’s other parodies are funny. Maybe what’s at stake is pleasure in the momentary refusal to take the artistic masterpieces seriously. When Tony Green, who is a very serious art historian, published Poussin’s Humor (2013), a publisher who laughed at the project said: ‘That will be a short book’. But he was wrong. It would be most interesting to have a general account of visual humor, and, also, to explain why some of Anthony’s images do not quite ‘come off’.

Anthony and I met every now and then, and I tried (and sadly failed) to publish a book about him. Late in life he remained a cult-figure, showing in Iceland and Denmark but not, so far as I know, recently in New York. Which is sad, for no artist who won the praise of Laurie Anderson, Jasper Johns, Ken Johnson, Roy Lichtenstein, Joseph Masheck, Philippe de Montebello, Larry Rivers, Robert Rosenblum, Barry Schwabsky, Roberta Smith and Leo Steinberg could be altogether uninteresting. And our art world is a great subject for parody, for there’s a lot of pretentious, unintentionally funny art. Every time I look at Anthony’s works, they lift up my spirits and inspire that most reliable response, involuntary laughter. How many artists can claim to be that successful?

NOTE

Two books by Sam Jedig, Deviant Draftsmanship. The Art of William Anthony (2021) and Ironic Icons. The Art of William Anthony (2013) survey his career. See also Paul Barolsky, Infinite Jest: Wit and Humor in Italian Renaissance Art (1978).

David Carrier is a philosopher who writes art criticism. His Aesthetic Theory, Abstract Art and Lawrence Carroll (Bloomsbury) and with Joachim Pissarro, Aesthetics of the Margins/ The Margins of Aesthetics: Wild Art Explained (Penn State University Press) were published in 2018. He is writing a book about the historic center of Naples, and with Pissarro he conducted a sequence of interviews with museum directors for Brooklyn Rail. He is a regular contributor to Hyperallergic.

The not-so Divine Comedy

”There is in the human condition a basic absurdity as well as an implacable nobility” – Albert Camus

“I’ve been accused of vulgarity. I say that’s bullshit.” – Mel Brooks

Who ever said that modern art was not supposed to be funny? Not William Anthony, that is for sure. While humor remains somewhat under recognized in the annals of modern art, Anthony’s oeuvre of more of than 50 years nevertheless proves that it constitutes a distinct artistic intelligence, profound and outrageous at the same time. In his drawings and paintings critical commentary on contemporary culture and subtle reflections on the concept of art blend with perverse, if not downright obscene fantasies in a skewed satire. They pose a witty and pointed comic challenge to our perception of the world as we known it through images, twisting and turning conventions, parodying clichés and subverting preconceptions. Whether they are appropriations of the works of classic and modern masters, covers for gay magazines, posters for Broadway shows, illustrations of the Bible (the only one Warhol could understand according to Warhol himself), W.W. II history and Western mythology, or cartoonish takes on social events or even his private life, Anthony goes to work on the images with his characteristic unorthodox and original pencil. In his eyes and hands no image, type, style or period, is too sacred to be exposed to a process of continuous interpretive mutation. He depicts the familiar in surreal, dumb, childish, grotesque, silly, vulgar, and disturbing ways that make you smile discretely (“Am I really allowed to think that Hitler making an excuse for his wrongdoings is funny and that War is Swell?”) or laugh out loud (I don’t care what other people, especially the feminists think, the story of “Tit Slapper” is hilarious). In either case, you seriously wonder about the sanity of the world and of the artist.

Iconic irony

Anthony identifies with a particular form or tradition of images, of image making and function of images, namely that of the icon, which is underlined by his recent paintings on wooden panels. Like the classical religious icons, Anthony’s icons are relatively small in size and their simple motives make references to imagery with a strong presence in the collective imagination of contemporary visual culture. However, their aesthetics and ethics differ quite significantly from these ancient gold-coated objects used as aids in praying. They are ironic icons in the sense that they make fun of the imagery that we “believe in” and “guide” us. Instead of portraying transcendental ideals they present us with the banalities, stupidities and faults of man, down to earth and below the waist. Right in our faces. SMAK! The spiritual and aesthetic authority of the icon is replaced by the irony of the human condition, stripped down to its naked bodily existence and its misguided behavior and self-conceptions.

The irony of Anthony’s icons is not a cool postmodern indifference or nihilism. On the contrary, it is an expression of honesty. From a perspective without illusions they depict man, this stereotypical creature walking the earth with a dumb grin of his face. Up to no good. This is how man really behaves, thinks, and looks behind the ideals of his narcissistic mirror; how he gets in his own way all the time and does not make a whole lot of sense. That is the irony Anthony deals with in his icons. Better believe it.

Don’t try this at home

Anthony’s characteristic style of drawing, which he also practices in his paintings, is not taught in art schools. Actually, it originates from a book he wrote back in the mid 60s entitled A New Approach to Figure Drawing where he – inspired by his student’s mistakes – used exaggerated and disproportioned figures as examples of how not to draw. But what happened was that, “this satirical how-not-to took on an insane life of its own in my work”, as he later put it in an interview. The mistakes liberated Anthony from the restrictions of the classical technique and concept of drawing and allowed him to embrace a new personal style that is way out of line and proud to be so.

As accidentally and inadvertently as this style came into being Anthony has developed and refined it to (im)perfection. Aesthetically, it holds the naiveté and simplicity of childrens’ drawings that play around with image making with an unmistakably touch of an adult’s skilled determination to abandon all rules, except from the rule not to follow rules. It is a stylistic deadpan joke told with such force and conviction that it is impossible to discard it as a matter of bad technique. The idiosyncratic logic of representation cannot be judged according to the classical ideals of depicting the human figure in the art. It is beyond that, mocking the aesthetic of the anatomically correct and soulful as an aesthetic of delusions and boredom. Man is not, or actually never was, an ideal figure, neither physically nor mentally; rather he has always been full of faults, inabilities, and pretty much two-dimensional and Anthony’s style reflects this. It resists absorption by the culture of beautiful and “correct” images, working instead on the far side of this culture, where puerile ideas and deviant desires that would even make Sigmund Freud feel at a loss of words guide the pencil.

Pop Art revisited and twisted

Springing from a pop cultural sensibility akin to that of his near-contemporaries Warhol and Lichtenstein (both big fans of Anthony and two of Anthony’s declared sources of inspiration) Anthony’s art is action-packed with a diversity of references to other images, from movies, photographs, magazines, paintings, and cartoons, you name it. In this sense, Anthony is a thoroughbred pop artist, but his works do not come in fancy and flashy colors. In fact, they could not give a rat’s ass about the shinny side of pop. In the spirit of graffiti culture, they rather thrive in the crude and trashy elements of pop and associate with street kids like Cy Twombly and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Their disturbed lines are all about getting dirty. Not just for show. Real dirty.

Anthony’s dedication to and involvement with the unpolished is also reflected in his choice of grotesque, dramatic and absurd subjects closely (if not explicitly) related to German Expressionism, Francis Bacon, Hieronymus Bosch and well, yes, Robert Crumb. However, when all these prominent references are mentioned, it is essential to note that Anthony does not fit into any unequivocal art historical contextualization. There is a particular indeterminability and timelessness to his art. Like the daily newspapers comics, it continues indefinitely, in its own disharmonic loony tune with the crooked and crazy way of the world (of images) without significant aesthetic changes, yet it still maintains an undeniable innovative freshness and unpredictability. You easily become familiar and fall in love with Anthony’s universe, but at the same time it keeps charmingly surprising and delightfully alienating you by expanding its territory, covering new land that you never imagined existed or dared to imagine existed.

One can say that in a world where God’s authority and promises seem ever more questionable laughing at the ludicrous and inexplicable aspect of human existence is the closest to transcendence man can get. To provoke this laughter seems to be the function of the ironic icons of St. William Anthony. They will not guide you the way to a higher ground, but they will take you on a hilarious detour at eye level – or in most cases, even lower – filled with revelations, unlike anything else in the world of images. Off we go. At full risk.

By Jacob Lillemose

Copyright @ All Rights Reserved